Here are the changes brought about by the future european ‘right to repair‘

Is the era of disposable items about to come to an end? At least, that’s the ambition of the directive on the right to repair proposed by the European Commission, which aims to put an end to the linear model by favouring repair over purchase. This new directive provides for new rights as well as incentives to make repairs more attractive and simpler, particularly after the expiry of the legal guarantee.

‘With today’s agreement, we are one step closer to establishing a consumer right to repair. In future, it will be easier and cheaper to have your products repaired than to buy new ones’, declared the reporter René Repasi (S&D, DE) at the end of the negotiations between the various EU bodies.

This new industrial shift will encourage manufacturers to design products that can be easily dismantled and repaired. Here’s how it works :

ELECTRONIC WASTE IS ON THE RISE, AND SO ARE ITS CONSEQUENCES FOR THE ENVIRONMENT

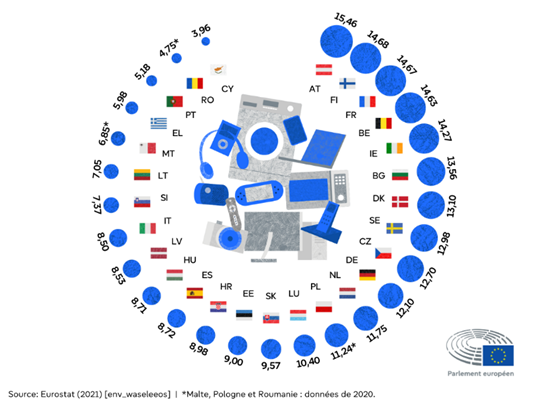

Eurostat data confirms the trend towards an increase in the number of electronic devices entering the EU market and, consequently, in the amount of waste generated.

- More than 13 million tonnes of equipment were sold in the EU in 2021, an increase of more than 85% since 2013.

- In 2021, 4.9 million tonnes of electronic waste were recorded (11 kg per person on average in the EU), 3.9% more than in 2020.

- Per resident, the biggest consumers of equipment in the EU are the Netherlands (35.1 kg), Germany (31.3 kg), Denmark (30.7 kg), France (30.5 kg) and Belgium (29.2 kg).

Waste electrical and electronic equipment in kg per resident

The constant renewal of household appliances is not without consequences for the environment. Their manufacture puts pressure on rare metals such as lithium, cobalt, iridium and copper, the extraction and processing of which affects the health of miners and residents in the extraction areas, as well as being very costly in terms of energy and water. By way of comparison, the production of a single smartphone requires 70kg of raw materials, i.e 583 times the weight of a single phone.

In the 1990s, mobile phones the size of bricks contained 29 metals. Today’s much smaller smartphone, paradoxically, contains up to 55 metals. We think we live in an immaterial world, but in fact it is considerably materialistic’, says Guillaume Pitron, author of the book La guerre des métaux rares.

Emilie Janots, lecturer and researcher at Grenoble Alpes University, adds that ‘rare earths have an ionic radius close to that of radioactive elements such as uranium and thorium. This is why they are often found in minerals containing rare earths, creating radioactive waste’ that can contaminate watercourses and cause acid rain. Electronic devices contain persistent organic pollutants (POPs) that can lead to the direct release of hydrocarbons into watercourses or surrounding areas when they decompose in the open air. For example, cathode ray tubes, commonly found in old televisions exported en masse to Africa and South-East Asia, present environmental risks if they are broken or if the screen is removed. These tubes contain lead and barium, which can seep into groundwater and release toxic phosphorescent substances.

Between 7% and 20% of WEEE produced in Europe are illegally exported, mainly to Africa, despite the 1992 Basel Convention banning the export of hazardous waste. The Mbeubeuss landfill receives waste from the Dakar region. Every day, waste pickers, informal workers, collect the recyclable waste dumped by bin lorries and sell it to wholesalers and companies.

© Jennifer Carlos / Reporterre

Since 2018 and China’s decision to close its door to toxic waste from abroad, some of it has ended up in Malaysia. The town of Segamat, located in the state of Johor, is home to one of the country’s largest illegal recycling plants. Currently, only low-value waste is processed in Malaysia, while higher-value waste is sent back to China, where it is accepted because it is less harmful.

© MANAN VATSYAYANA – AFP

THE RIGHT TO REPAIR AS AN ALTERNATIVE TO DISPOSABILITY

On 1 February, the European Parliament and the Council of the European Union reached a political agreement on a proposal for a directive from the European Commission aimed at encouraging the repair of broken or defective goods.

The text introduces a stronger right to repair for consumers on a wide range of appliances such as washing machines, dishwashers, fridges, hoovers and mobile phones.

As well as reducing the volume of waste, Brussels hopes to put an end to programmed obsolescence, while creating new economic opportunities.

‘With today’s agreement, Europe is clearly making the choice to repair rather than throw away. By making it easier to repair faulty products, we are not only giving our products a new lease of life, we are also creating quality jobs, reducing our waste, limiting our dependence on foreign raw materials and protecting our environment’, said Alexia Bertrand, Belgian Secretary of State for the Budget and Consumer Protection, when the agreement was announced.

However, Agnès Crepet, Software Sustainability Manager at Fairphone, regrets the absence of any mention of independent repairers, ‘whose interests seem to me to be less well defended.'[…] These repairers only have access to spare parts from certain brands at dissuasive prices. ‘We’ll see what the prices are, but I’m not optimistic’.

In 2014, a study carried out by the European Commission revealed that 77% of Europeans questioned preferred to repair rather than throw things away, but were prevented from doing so by high costs, limited repair services and a lack of spare parts.

In France, although consumers have a positive image of repair, which they associate mainly with an ecological act, the practice remains in the minority. In fact, according to a 2019 study entitled Les Français et la réparation: Perceptions et pratiques carried out by Harris Interactive on behalf of ADEME, 54% of the French people questioned choose to replace a broken product rather than repair it. The cost of repair is the main obstacle, cited by 68% of them.

OVERVIEW OF THE NEW RULES

The new rules aim to facilitate access to repair services by making them faster, more transparent and more attractive.

During the two-year legal guarantee period, consumers will have a choice between repair and replacement. Repair must be free of charge, unless it proves more expensive than replacement or repair is impossible. The manufacturer must also continue to offer affordable repairs, even if the product is no longer covered by the warranty.

In addition, any repair will entitle you to a one-year extension of the warranty. During the repair period, it will be possible to borrow a replacement appliance.

Free online access to an assessment of repair prices must be available. At the consumer’s request, repairers will have to submit a harmonised estimate, known as a ‘European repair information form’. This form will contain pricing information such as the type of repair proposed, its price or, if the precise cost cannot be calculated, the calculation method applicable and the maximum price of the repair.

A single platform, designed and managed at European level, will be put online to make it easier for consumers and repairers to get in touch. Sections will be reserved for each Member State, with information also coming from national repair platforms, and access to Community repair initiatives.

Manufacturers will have to comply with a number of constraints. Firstly, they will have to offer spare parts at a reasonable price so as not to discourage repair. The agreement also prohibits manufacturers from putting in place barriers to repair, such as the use of proprietary software or hardware that prevents independent repairers from repairing products.

Finally, each Member State will be required to introduce at least one measure to promote repair. These could include repair bonuses and funds, information campaigns, repair courses, support for the development of repair facilities or reduced VAT rates on repair services.

ENCOURAGING REPAIR: THE EXAMPLE OF THE FRENCH REPAIR BONUS

In France, this directive comes on top of the Repair Bonus proposed by the government to extend the life of equipment.

Launched at the end of 2022, this scheme covers part of the repair costs for a wide range of 73 products. The premiums range from €15 to €60 and represent an average of 17% of the total cost of repairs. Thanks to these bonuses, consumers can benefit from a reduction in their repair bill, provided they visit one of the 4,700 QualiRépar approved repairers.

In 2023, 165,000 repairs benefited from this bonus, for a total amount of €4 million covered by the eco-organisations thanks to the repair fund financed by contributions from manufacturers as part of the extended producer responsibility (EPR) scheme.

This is eleven times less than the budget set out in the specifications for the eco-organisations approved for the EEE sector’, explains Bénédicte Kjær-Kahlat, Legal Manager at Zero Waste France.

One year after its launch, the results are still mixed: in 2023, the premium was used for only 0.2% of breakdowns and 1.7% of out-of-warranty repairs. These are the findings of a study carried out by the Halte à l’obsolescence programmée (HOP) association, which highlights other shortcomings, such as the lack of repairers (74% of non-approved repairers consider the cost of approval to be too high, and 52% consider the reimbursement period to be too long), the complexity of the procedures, overly discreet communication, and insufficient reimbursement amounts.

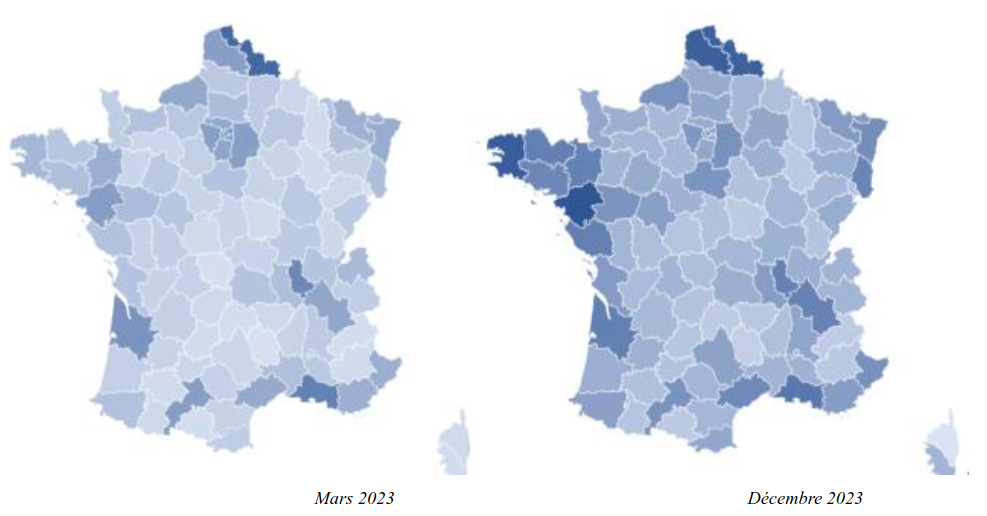

For its part, in a study published at the beginning of the year, the national consumer and user defence association CLCV noted a 10-15% increase in the average cost of repairs linked to premiums, as well as geographical disparities in access to repairs. Some areas are less well served than others in terms of the number of approved repairers in relation to population density. These inequalities have a significant impact on the use of repairs, as excessively long repair times can discourage consumers, who often opt for the convenience and speed of replacement.

Changes in the density of repair outlets between March 2023 and December 2023 © CLCV

Nathalie Yserd, Ecosystem’s Managing Director, points out that the fund is still in its start-up phase. The mandate we have been given is to mobilise (and therefore spend) just over €500 million on this fund over a period of 6 years’, she explains.

To stimulate repair, the government has taken a series of measures from 1 January 2024: a €5 increase in the amount of the bonus for 21 appliances, a doubling of the bonus for 5 appliances (from €15 to €40 for hoovers, from €25 to €50 for washing machines, dishwashers and tumble dryers, and from €30 to €60 for televisions), and the inclusion of 24 new appliances such as epilators, hairdryers or printers.

For repairers, efforts will be made to simplify and shorten reimbursement times, with a commitment to reimburse within 15 days and the introduction of a single reimbursement platform, as well as a simplification of the QualiRépar certification process.

ELSEWHERE IN EUROPE: TAX MEASURES TO ENCOURAGE REPAIRS

Several European countries have tackled the disposable culture by offering incentives.

Since 2017, Sweden has applied a reduced VAT rate of 12% (25% before the bill was passed) for the repair of bicycles, washing machines, clothing, leather goods and household linen.

In 2016, Swedish Finance Minister Per Bolund justified the new measures as follows: ‘We think this could reduce costs and make repairs more rational and economical. There is a change in this area in Sweden at the moment, an awareness of the need to make objects last longer in order to reduce the consumption of materials.

Tax credits also allow Swedes to deduct half the cost of repairs to household appliances such as ovens, dishwashers and washing machines from their tax bill.

In Austria, since May 2022, the government has subsidised 50% of the cost of repairing a faulty electrical appliance, up to a maximum of €200. Designed to encourage circular practices and combat e-waste, this support measure, known as the ‘Reparatur Bonus’, covers half the cost of repairs to smartphones, laptops, coffee makers, dishwashers and a number of other appliances. Since its introduction, 560,000 vouchers worth up to €200 have been used, far exceeding the 400,000 hoped for by 2026.

The only constraint is that the repair voucher must be requested on thethereparaturbonus.atwebsite and used within three weeks of payment of the bill.

In the UK, from July 2021, the Right to Repair Regulations require manufacturers to make spare parts available for electrical appliances within two years of the launch of each model. Parts must also be available between seven and ten years after the model ceases production.

At present, the law only covers dishwashers, washing machines, tumble dryers, refrigeration appliances, televisions and monitors. It does not cover mobile phones or laptops, and there is no cap on the cost of repairs.

In October 2023, 110 UK groups signed a statement on repair and reuse calling on the UK government to make repair more affordable and extend the regulation to all consumer products.

Communication campaign by The Restart Project for National Repair Days.

NEXT STEP

Once the directive has been published in the EU’s Official Journal, Member States will have 24 months to comply with it and transpose the right to repair into their national legislation.

It is important to note that a directive is different from a regulation. Regulations apply directly, without the need to incorporate them into national legislation. Directives, on the other hand, must first be translated or transposed in the Member States. This means that Member States have some leeway to adapt European legislation to their needs.